When you think of London’s skyline, you probably picture the city’s iconic landmarks such as the Houses of Parliament, St Paul’s Cathedral, Tower Bridge, and the Shard. Yet all these famous sites would be completely dwarfed by a construction that was proposed nearly two hundred years ago. It would have stood 94 storeys tall, covered 18 acres, and housed the remains of some five million dead Londoners. This is the history of the Metropolitan Sepulchre.

By the early 19th century, London had become the largest city in the world. Its population had swelled from around 750,000 in 1760 to over 1.4 million by 1815. The city’s rapid growth was fuelled by the advancements made during the Industrial Revolution, which brought massive influxes of people from the surrounding areas into the nation’s capital in search of work. This transformed the city into a teeming metropolis, but its infrastructure failed to keep pace and soon began to struggle with supporting the exponentially increasing population. Not only did this pose problems for London’s living citizens, who required housing, sanitation, and transportation, but it also raised the question of what was to be done with them when they were dead.

For centuries, London’s deceased had been interred in local parish graveyards, but these were now well beyond capacity and no longer fit for purpose. Traditional burial grounds were never designed to accommodate such numbers, and as a result, corpses were often laid out in shallow graves, layered one atop another, with only a thin covering of soil separating the remains from the surface. When space ran out, older graves were exhumed, and the bones of the deceased were discarded to make room for new burials. The smell of decomposition permeated the air, and the graveyards became breeding grounds for disease, heightening fears about the health risks posed by the overcrowded burial grounds. Cholera outbreaks, which ravaged the city in the early 19th century, only intensified these concerns.

This issue, however, was not new. As early as the 17th century, Sir Christopher Wren had proposed relocating London’s burial grounds to the outskirts of the city, but his suggestion went unheeded. By the 19th century, however, the situation could no longer be ignored, and so reformers, architects, and entrepreneurs offered various solutions to the city’s morbid problem.

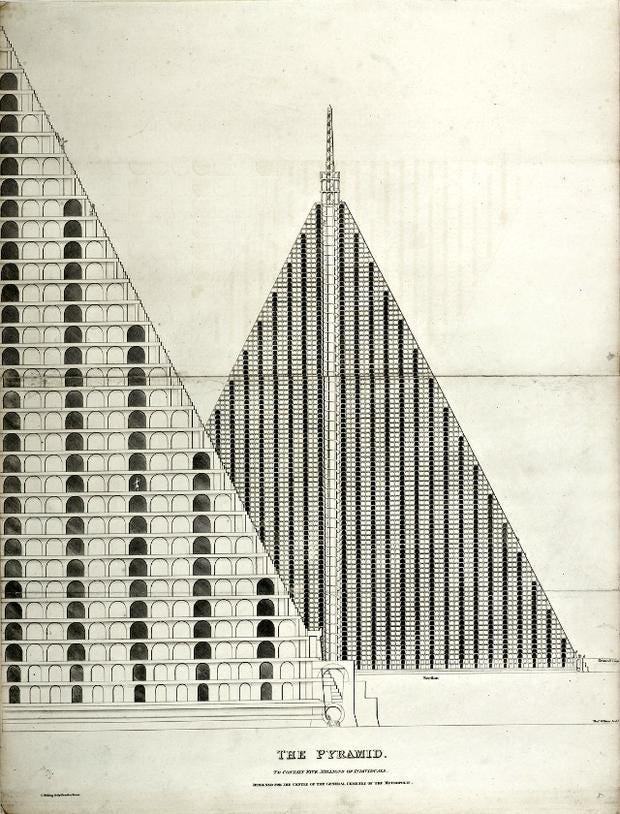

One of these proponents was Thomas Willson, an ambitious architect who devised a solution as radical as the problem it sought to address. In 1829, he proposed constructing a massive pyramid—the Metropolitan Sepulchre—atop Primrose Hill in North London. The structure would be 94 storeys tall, with a base covering 18 acres and a total capacity sufficient to house the remains of five million Londoners.

Willson’s pyramid was conceived as both a practical solution to the burial crisis and a monumental architectural statement. Its design drew inspiration from ancient Egypt and tapped into the latest Victorian trend of the time: Egyptology. European interest in the ancient civilisation had gained massive popularity in the preceding years, and British museums and exhibitions quickly capitalised on the public’s enthusiasm for the subject. The Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, for example, hosted popular displays of artefacts and reconstructions of Egyptian tombs. Willson’s design aimed to evoke the mystique and permanence of Egyptian burial practices, while at the same time presenting his pyramid as a modern yet timeless monument to eternity.

The pyramid itself was meticulously planned, featuring several concentric corridors per floor, with vaults lining each corridor. Each vault could hold 24 bodies, and the floors were connected by ramps to facilitate access for funeral parties. As the pyramid rose, the number of corridors per floor decreased, creating a stepped effect. The structure was to be built from brick and faced with granite, ensuring both durability and grandeur. It featured flights of stairs on every side, leading to an obelisk and astronomical observatory at the pyramid's peak. Willson even incorporated administrative offices, a chapel, and staff quarters into the design, making the pyramid a self-contained necropolis.

The Metropolitan Sepulchre was more than just a visionary architectural project; it was also a shrewd business proposition. Willson formed the Pyramid General Cemetery Company to promote and fund the project. He estimated that each vault could be sold for £50, offering burial space for families, parishes, or other organisations. With a projected annual intake of 40,000 burials, Willson calculated that the pyramid would generate profits of £10 million for the company’s investors – which, in today’s terms, amounts to well over £927 million.

The location of Primrose Hill was also strategically chosen. Situated in an open area yet still within close proximity to London’s urban core, it offered easy access and would be visible for miles around due to the pyramid’s towering height. Culturally, the pyramid resonated with contemporary attitudes towards death. While Victorian society was not yet fully immersed in the elaborate mourning rituals that would define the latter half of the era, there was a growing fascination with the afterlife. Willson’s pyramid capitalised on this interest, offering a vision of death that combined grandeur, permanence, and modern efficiency.

Despite its ingenuity, the Metropolitan Sepulchre faced significant opposition. Critics ridiculed the concept as impractical, dehumanising, and even grotesque. The pyramid’s labyrinth of corridors and uniform vaults evoked comparisons to industrial warehouses and factories, leading some to question whether it could provide the dignity expected of a burial ground. Satirists imagined mourners wandering endlessly through its corridors in search of deceased loved ones, turning what should have been a place of solace into a bureaucratic nightmare.

The timing of Willson’s proposal also worked against him. In the 1830s, an alternative solution to the burial crisis was gaining traction: garden cemeteries. Inspired by the picturesque Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, these landscaped burial grounds offered a more romanticised vision of death, blending nature, art, and reverence. Ultimately, the garden cemetery movement proved more popular and politically palatable than Willson’s pyramid, with seven large private cemeteries being created across London at sites like Highgate and Kensal Green. The British Parliament rejected the Metropolitan Sepulchre in favour of these more conventional, albeit innovative, burial grounds, which promised tranquillity and dignity and were more appealing to a public increasingly dissatisfied with overcrowded urban graveyards.

In the end, London chose a quieter, more human-centred approach to death. Although the Metropolitan Sepulchre was never built, its legacy endures as a fascinating “what if” in the history of London. Models and plans of the pyramid were displayed at subsequent exhibitions, where they continued to attract both admiration and ridicule. Over time, some historians and architects have re-evaluated Willson’s vision, recognising it as an extraordinary example of Victorian ambition and ingenuity. Had the pyramid been constructed, it would have dramatically altered London’s skyline, likely becoming one of the city’s most iconic landmarks. Its size and symbolism would have overshadowed Big Ben and even St Paul’s Cathedral, and its influence might have inspired other architectural designs during that period, which would have dramatically changed the aesthetic of London from that of which we are so familiar with today.

Share this post