How the East India Company Took Over An Entire Country

The city of London has been the centre of Britain’s economic and commercial activity for centuries, with many of the largest and wealthiest companies in the world choosing to locate their headquarters in the nation’s capital to this day. However, none of these modern businesses can compare to what was undoubtedly the most powerful multinational corporation the world has ever seen. Established over 400 years ago, the East India Company, from it’s headquarters on Leadenhall Street, would rise from humble beginnings as a trading company for voyages to India; to effectively becoming the de facto state government of the entire sub-continent.

During it’s heyday, the Company would surpass the strength and wealth of even the mightiest nation states, and with it’s own private armies, would push aside the long established native dynasties of India, seizing control of their territories for itself. All this would be achieved by maintaining an iron grip on the most valuable trade routes in the world, which generated staggering amounts of wealth for it’s employees and shareholders. But how did this private corporation come to rule over one of the largest and richest regions on earth in the first place?

This is the history of the East India Company.

The establishment of the East India Company dates to the turn of the 17th century. Although, it was not the first such company to be founded during this period for the purpose of establishing overseas trade. Up until this point, only Spain and Portugal had successfully carved out large empires of their own across the world but having become aware of the benefits and riches that could be gained from such ventures, several other European nations became increasingly eager to establish overseas colonies for themselves, particularly the Kingdoms of England, France and the Dutch Republic.

The governments of these nations, however, could often not afford to sponsor the costly and inherently risky expeditions. As a result, in the sixteenth century, merchants and politicians in cities like London and Amsterdam began to set up what would later become known as joint-stock companies. These were the first modern corporations, in so far that citizens of these cities could invest their money in companies which would organise colonisation missions or trading expeditions overseas. If these expeditions were successful in developing lucrative trade contracts or setting up colonies, the investors would receive a share of the profits as a return on their initial investment.

The first company to be set up in such a manner, was that of the Muscovy Company in 1555, through which English merchants organised trade missions to what is now Moscow in Russia. Despite it’s successes, London’s merchants were well aware that the real prize in world trade was to be found in the Far East; with India, China and the East Indies. The goods which could be brought back to Europe from there, such as pepper, cinnamon, nutmeg, tea and silk could fetch more than their weight in gold. Consequently, in 1600 a group of prominent London merchants petitioned Queen Elizabeth I to grant a charter to their newly founded company called the ‘Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading into the East Indies’. The charter was granted and the company under it’s governor and board of 24 directors, shortly thereafter dispatched it’s first small fleet of ships to the East Indies.

The East India Company was by no means an overnight success. During it’s first few years, the expeditions that set sail to trade with what is now Malaysia and Indonesia, encountered stiff competition from the Dutch East India Company and the Portuguese crown, both of whom were already well established in the region. By the 1610’s however, progress had been made by acquiring some concessions from the rulers of various parts of coastal India, who granted permission for the English merchants to trade in their ports. Later, in 1639 the Company purchased a stretch of land on the south-eastern coast of India. The colony of Madras which was subsequently established here became the first major foothold on the sub-continent. This was added to further in 1661 when, as part of a diplomatic alliance between England and Portugal, the Portuguese colony of Bombay was gifted to England. The East India Company soon established itself there as well, and thus, by the second half of the seventeenth century, there were numerous coastal colonies that the Company would look to expand itself further from in the coming decades.

The activities of the East India Company were not confined entirely to the continent of Asia. While they did little to intervene in the Americas, where other joint-stock companies had monopolies from the English crown, they did involve themselves from an early stage in the African slave trade. Not long after the Company had established it’s presence in India, it began purchasing slaves from parts of Eastern Africa, such as Mozambique and Madagascar, in order to avoid a conflict of interest with the Royal African Company which controlled the slave trade on the Western coast of the continent. But unlike the Royal African Company, the East India Company did not focus on transporting large numbers of slaves across the Atlantic to the Americas and instead shipped slaves across the Indian Ocean to India and the East Indies. Many of these slaves were forced to work in the Company’s factories and workshops in places like Madras and Bombay, where cheap labour was used to increase shareholder profits back in London.

Throughout the remainder of the 1600’s, the East India Company grew modestly but for the most part was overshadowed by it’s larger and more competitive Dutch counterpart. Tensions between the two trading companies grew and eventually escalated into a series of conflicts between their respective nations, with the Anglo-Dutch Wars being fought in the latter half of the 17th century. The company’s fortunes would change for the better in the following century however, with a series of military conquests in India which would set it on the path to becoming the most powerful corporation in human history.

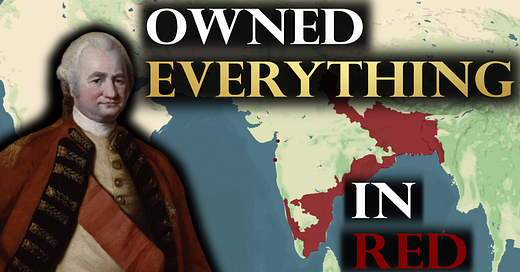

A key figure to the success of the East India Company during this period, is that of Robert Clive. Having joined the company at just 20 years of age, Clive quickly rose through the ranks during the late 1740’s and by the early 1750s, had become a senior officer within its operations in India. By this point, the Company had recruited thousands of British and Irish soldiers for its own private army and had gained allies amongst the smaller states of India, through which it could call on for reinforcements in the event of military engagements. It was this military power that Clive would learn to mastermind and subsequently deploy in a strategic move against the Nawab of Bengal, in 1757. The Battle of Plassey which was fought that year saw a small British force, aided by modern artillery and rifles, defeat a numerically superior, Bengalese army numbering in the tens of thousands. Victory at Plassey allowed Clive and the East India Company to take control over the extensive region of Bengal in the years that followed. This was the first major development for the Company’s rule in India, which saw it expand from a handful of ports and factories, to acquiring direct control over an extensive piece of territory.

In the decades that followed, Clive and other officers of the East India Company continued the policy of territorial expansion across the subcontinent. This was often at the expense of small native princes and Nawab’s that controlled local provinces. However, three great powers lay to the west of the Company’s main presence in Bengal, namely: the Mughal Empire, which ruled much of northern India and Pakistan, the Maratha Confederacy, which dominated central India, and the Sultanate of Mysore, the predominant native power in the south. The French were also attempting to exert their power and influence in southern India during this time, from ports like Pondicherry. Although, the outbreak of the Seven Years War, which was fought between Britain and France across the world from 1756 to 1763, gifted the likes of Clive an opportunity to halt to the French advance in India, which he did successfully.

Almost half a century of perpetual war followed between the East India Company and the countries native powers. Four wars were fought against Mysore alone between 1767 and 1799. To keep up with the demand for this seemingly never-ending warfare, the Company began hiring tens of thousands of native troops called Sepoys, so much so that by 1800, it employed well over 200,000 soldiers, an army greater in size than that of many developed European nations of the time. It was with this enormous military force and infinitely superior military technology, that the East India Company was able to finally conquer the city of Delhi in 1803. Despite resistance from powers such as the Maratha’s, which continued on a small scale for several years, the Company was effectively in control of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh by the early nineteenth century.

Unsurprisingly, given the vast scale of the East India Company’s operations, it was able to generate enormous profits for its shareholders back in London. Not only did the Company control a huge swathe of territory across India, but it also exercised a monopoly on all British trade in and out of the region. For every cup of Indian tea which was drank in Britain from 1600 to the mid-nineteenth century, the East India Company provided it. Additionally, from the 1750’s, the Company also began to benefit from the taxation of the millions of Indian subjects under it’s rule.

Although the Company’s military and commercial ventures in India were successful, it’s civil governance of the territory was by comparison, servery inadequate. The most catastrophic example of this was the Bengal famine of 1770, which due to the Company’s inept handling of, resulted in the deaths of approximately ten million people across north-eastern India. Despite a damning report of the Company’s response to the crisis produced in 1772, by the first Governor-General of Bengal, Warren Hastings, it was overlooked by the Company’s board of directors and administrators back in London, whose primary interest remained bottom line profit.

It should be noted that India was not the sole area of interest for the East India Company. Throughout its history, it also had interests further to the east in what is today Malaysia and Indonesia, as well as in China and Japan. In the 19th century, the latter two countries tried to prevent any contact whatsoever with European traders, outside of a few select ports. However, as the technological gap between Europe and Asia widened, the Chinese and Japanese would become powerless to prevent the likes of the British from forcing their way into their dominions.

The most profitable trade for the East India Company at this time was that of opium, which was produced in India and exported primarily to China. The Chinese attempted to push back against this highly addictive and damaging commodity, by seizing opium stocks from merchants and threatening to impose the death penalty upon anyone dealing in the trade. The East India Company, alongside the British government, retaliated by declaring war on the Qing Dynasty of China in 1839, in what became known as the First Opium War. By it’s conclusion in 1842, the British had seized control of Hong Kong Island and the Qing Dynasty was forced to abandon it policy of isolation and reluctantly open it’s ports to British and other European merchants.

In little over 200 years, the East India Company had expanded from a handful of coastal trading posts, to controlling some of the most valuable lands and trade routes in the world, however, nothing could prepare it for the calamitous and abrupt downfall that was to come. In 1857, a widespread native rebellion against Company rule broke out across India. This was driven by a wide range of grievances, many of them concerning the methods of governance that the East India Company had employed. For instance, there was a perception that the taxes which the Company had imposed in the country for decades were excessive and many of the local Indian nobles and princes, whose ancestors had ruled the kingdoms and states that had been annexed by the Company since the eighteenth century, believed it was now time for them to reassert their independence. Certain parts of the country, such as Bengal and the old colonies of Madras and Bombay, were relatively unaffected by the revolt. Although other regions, particularly in the north around Delhi, witnessed Company control collapse entirely, with many of the native Sepoy troops on the Company’s payroll joining the rebellion.

The Indian Mutiny lasted for well over a year and claimed the lives of over 6,000 British civilians and employees of the Company, as well as an estimated 800,000 Indians who fell victim to not only the violence itself but also the subsequent outbreaks of famine and disease in the aftermath of the revolt. This catalogue of serious failings confirmed to the British government that the East India Company was no longer capable nor trustworthy to govern the country effectively. Subsequently, in August 1858, the ‘Government of India Act’ was passed by the British Parliament, which transferred all the territories under the control of the East India Company, to the possession of the British Crown. India was to then be ruled under a direct system of governance as part of the British Empire.

The events of 1858, however, did not bring the East India Company to a complete end. Although it was now effectively nationalised, with all its assets including land holdings, civil service and military operations taken under state ownership, the Company could not be wound down entirely owing to an agreement with the British government which had previously been reached in 1833. This stipulated that the Company’s shareholders were to receive a 10.5% dividend on their shares every year for 40 years, in return for greater government scrutiny of the Company’s affairs and management of India. Owing to this agreement, there was a legal requirement for the British government to not dissolve the Company in full until 1873, when the forty-year term would expire.

In the interim period, the Company continued to carry out numerous functions, including the management of the tea trade in and out of India. When the end came though in 1873, the British parliament passed the ‘East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act’ which formally dissolved the Company and provided the final restitution of compensation to it’s shareholders. The British presence and rule in India however, continued for another 70 years until 1947, when the country alongside what is now Pakistan, was granted full independence.

By comparison to modern multinational businesses who are often deemed as ‘too big to fail’, the East India Company with its vast territorial possessions, invaluable trade monopolies and private military force, simply became too big to be allowed to continue to exist.